Freshwater, Akwaeke Emezi

Akwaeke Emezi’s spellbinding, haunting debut novel Freshwater (nominated for the 2019 Women’s Prize for fiction) tells the story of Ada, a young Nigerian Igbo and Sri Lankan Tamil woman who is an Ogbanje. She is “spirit and human, both and neither.” According to Igbo ontology, an Ogbanje is a spirit child that torments its parents by dying during its infancy. Sometimes, an Ogbanje may live into teens or early twenties. The same Ogbanje may die, be reborn as another child and then die again in one family. Partially rooted in Emezi’s own life experiences as a non-binary trans Ogbanje, Freshwater explores what it is like to dwell in liminal spaces. It is about being in between cultures, life and death, body and spirit.

Unlike other Ogbanje, Ada does not die. She witnesses her sister Anuli’s car accident, lives through her parents’ separation and, at seventeen, leaves her birthplace of Umuahia, Nigeria for college in the United States. Throughout it all, Ada is faced with nightmares, self-harm, and a suicide attempt as consequences for remaining in the living world for too long. Emezi writes with mesmerizing lyricism and their descriptions are incredibly vivid.; Ada does not just wake up from bad dreams — she has to “drag herself out through glutinous layers of consciousness.”

Narrated by Ada’s multiple selves, Freshwater is written in nonlinear prose that reflects Ada’s tortuous, agonising evolution from childhood to adulthood. The multiple voices narrating Freshwater do not jar. Rather, they are like pieces of a mosaic that form a variegated whole.

From the poised, melodious first person “We” (a collection of Ada’s various characters) to the assertive Asughara (one of Ada’s selves), they remind us that Ada is a “compound full of bones, translucent thousands.”

Ada’s fragmented existence is discussed by deities like Santa Marta, Chango and Yshwa that she meets throughout the course of her life. She first encounters Yshwa as a child during Catholic Mass. Ada prays to Yshwa and he watches over her, running “his hands along the curve of her faith.” In one particularly charged scene, him and Asughara, argue about their places in Ada’s life. Yshwa is adamant that he can save Ada’s life but Asughara, with her fervent jealousy, makes sure that he never gets too close to Ada. In this explosive part of the novel, we see how the gods that battle for Ada are guided not by goodwill, but by their own egos, and that their sense of pride comes first above everything.

An astonishing, confident debut, Freshwater implores us to suspend binaries such as human and non-human, western and non-western, male and female. Instead, we learn to view Ada’s world as a kaleidoscope of cultures, times, and ways of being. Freshwater is about learning to live with “one foot on the other side” and embracing liminality as reality.

Unanswerable, Lorna Simpson

Since the beginning of her career in the 1980s, American artist Lorna Simpson has been celebrated for her razor-sharp explorations of race, performance and gender. Many of her works such as Square Deal (1990) and Guarded Conditions (1989), utilize fragmented photographs of black American women to challenge the sexualisation and dehumanisation of the Black body. At the heart of Simpson’s striking, innovative works is a study of intersectionality - the ways in which classism, sexism and racism often interact and overlap. In Unanswerable at Hauser & Wirth, Simpson’s first London solo exhibition, photography, painting and sculpture come together in works that ponder on what it means to be American today.

The exhibition opens with Unanswerable, an installation that consists of forty individual photo collages that Simpson has created using original source material and archive photography. Simpson splices mostly Black female figures with animals, architecture and nature to create bizzare, dazzling images. One collage depicts a woman proudly showing us her wings. In another, a woman with the bottom half of her body on fire, calmly gazes into our eyes. While Unanswerable is mystical and playful, it also alludes to common ways in which we conceptualise the human body. For instance, in an image in which Simpson juxtaposes the head of a female figure with what appears to be a male body, we are forced to see past binary categorisations of the body as male or female. Simpson compels us to question the ways that we use gender to construct our world.

Ice is a recurring motif in this exhibition. In one collage, a woman comfortably sits on a throne made of ice. She smiles, seemingly unfazed by the cold. It as though she is telling us that she is here to stay, no matter what. The ice, here, might symbolise oppression and the other pains women and people of colour suffer in their day-to-day lives. Woman on Snowball is a sculpture of a female figure resting on top of a gigantic snowball. The snow, which her black head and neck are distinct from but the rest of her body that is white seamlessly merges with, seems to reflect her state of mind: a paralysis that could be caused by endless cycles of racism and sexism in the United States.

Lorna Simpson, Woman on Snowball, 2018. Styrofoam, plywood, plaster, steel, epoxy coating. 276.9 x 209.9cm / 109 x 82 5/8in. © Lorna Simpson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Simpson’s collection of vintage Ebony and Jet magazines - and photographs from individual issues - features prominently in this exhibition. These publications, which cover culture, lifestyle and politics from a Black American perspective, have shaped her thinking on being Black in America. Simpson also explains that they evoke memories of her childhood and are “a lens through which to see the past fifty years of history.” In 5 Properties and 12 Stacks, large ice blocks made from glass - just low enough for us to be able to peer into them from above - stand like totems on top of piles of the magazines, both magnifying and obfuscating the text and images of the magazine covers. “There’s something about ice that has come into the work that indicates either freezing or endurance,” Simpson says. Perhaps these “frozen” images of Black subjects indicate how Black people in the United States have been and are still being made to endure institutional racism.

Lorna Simpson, 5 Properties, 2018. Ebony and Jet magazines, poly sleeves, bronze, plaster, glass. 114.6 x 33 x 44.5cm/ 45 1/8 x 17 1/2in. © Lorna Simpson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Simpson’s large-scale 2D works on fibreglass, which straddle the border between painting and photography, convey calamity and doom. Images of glaciers and thick plumes of smoke, taken from Associated Press photographs are washed over with blue and black inks. In these works that do not include any human subjects, Simpson revisits her practice of combining images with text. Small strips of broken text that are layered with the found images complicate our reading of these pieces. As I tried to make out what the words were, my initial interpretation of these images as alluding to environmental catastrophes expanded. Fragments of words and phrases, including ‘blac’, ‘slav’ and ‘towa’ brought to mind other types of “catastrophes” - violence against Black people, most recently police brutality in the United States and protests by White supremacists. In these images of smoke contrasted with ice, I saw the turmoil that violence and other types of racism against Black people has created in the country, not just in recent times, but also in the past. For me, it was a chilling reminder of how little has changed.

While Simpson often presents a bleak, dark picture of the United States, we are also shown the resilience of Black Americans. Women are trapped beneath blocks of ice in 5 Properties and 12 Stacks, reminding us of the injustice and systems of power that have characterised so many Black women’s lives. In other images in which Black subjects sit on objects made of ice, we see how Black people thrive, even in the midst of tortuous conditions. With daily reports of murders of innocent Black people by the police, and of racial and sexual harassment across American societies, it seems like the country has been frozen in a state that oppresses many and favours a few. But the impermanence of the ice reminds us that these systems of oppression can be destroyed and be replaced with justice, freedom and peace.

Power Figures, Alexis Peskine

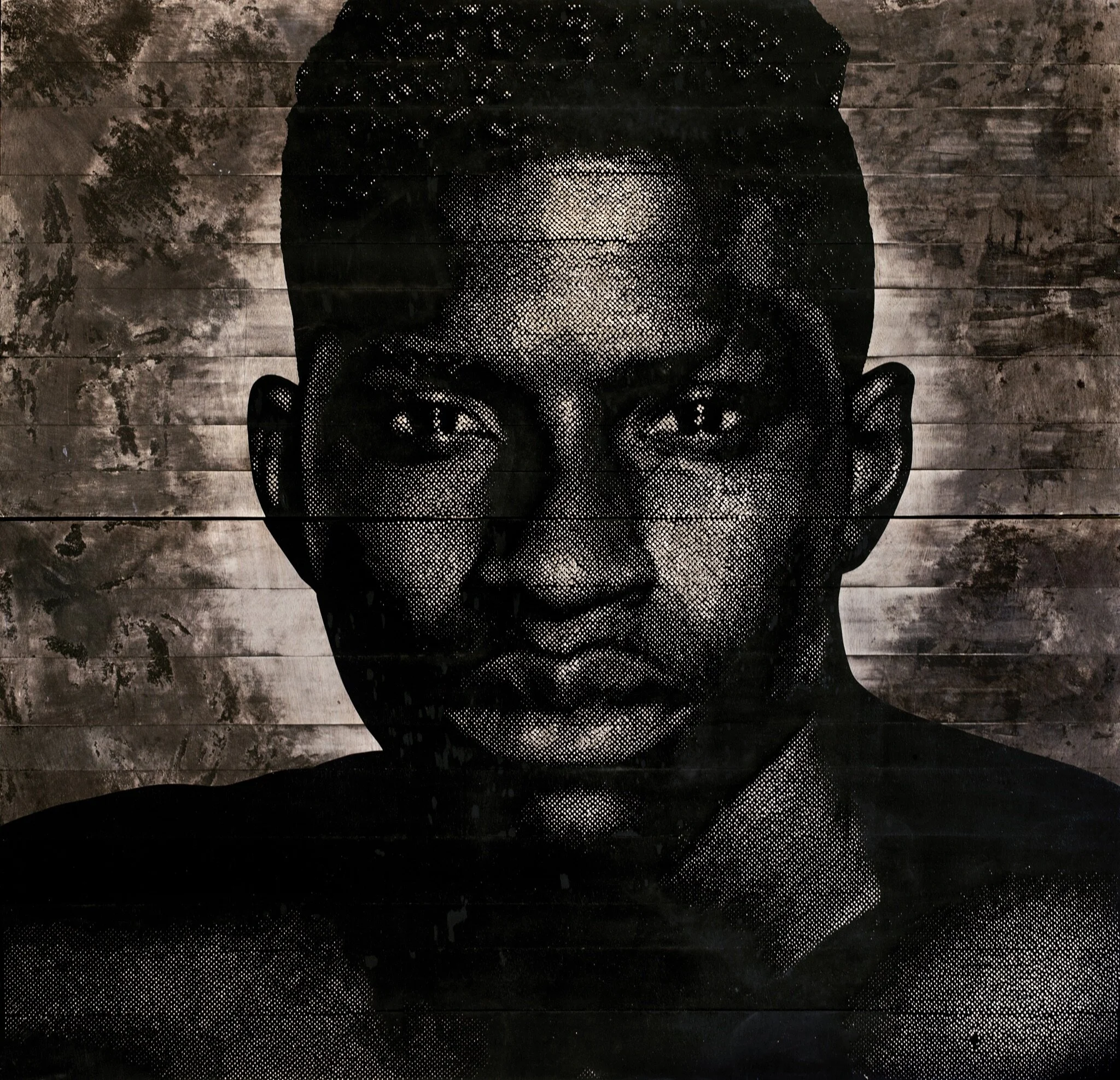

Grand portraits of Black faces tower above us at the October gallery. Nails with gold leaf applied to their tips form the features and give them their golden hues. Earth, water and coffee are combined to create the brown shade of the portraits’ wooden backgrounds. These are Power Figures, artist Alexis Peskine’s signature works that use portraiture to tackle questions of Blackness, identity and the African diasporan experience. I sat down with Peskine on the 15th of September after the opening of his first solo U.K exhibition. Having grown up in Paris but having spent time in the U.S, Dakar, Ethiopia, and Jamaica, Peskine has - he explains - always been “touched and marked by questions of identity.” He tells me that his encounters with racism, especially in France, have always made him angry. It is this anger that implores him to explore and challenge prevalent negative representations of Black people in images, through his work.

Alexis Peskine, Soninké Whispers, 2017. Nails, moon gold leaf, paint and satin varnish on wood panel, 241 x 247 cm. Courtesy October Gallery.

Peskine constructs his portraits using nails as a reference to the Minkisi power figures of Congo, that offer protection from evil spirits. He explains to me that the act of hammering nails into his subject’s faces highlights time and memory of the body by providing literal manifestations of pain, injustice and nobility. For him, the body is a “psychological” object, not just a “physical” one, as it is the initial passage through which our experiences - sensations, touch, sound and so on - pass through before we “feel” and react to them. However, the nails with gold leaf, he says, concurrently dignify his subjects. They subvert the manner in which photography has been used, in the past (and, still, now), to manipulate Africa’s histories, cultures and peoples into negative stereotypes and, instead, offer healing and positive ways of seeing the Black body.

In Power Figures, the subjects appear strong and poised but at the same time, there is a softness about them. Peskine tells me that depicting his subjects as gentle is radical - an act of “reclaiming the humanity” of his Black subjects. “We are either seen as hypermasculine, hyperstrong or hypersexual. The softness is something you seldom see in us,” he says. When Peskine describes how our bodies internalise and respond to imagery, the significance of portraying the tenderness in his subjects becomes even more potent. “We are seen as thugs, as lethal people… and it’s crazy because it affects us, in our bodies. We are conditioned to behave in a certain way, to not make people afraid of us,” Peskine says. He explains to me how images of Black men have affected him: “I catch myself doing things just because I don’t want to scare people, because I’m a big, Black man. I’ve caught myself crossing the street so that I don’t scare women at night but it’s terrible.” It becomes clear how especially important it is to show alternative images of Black people. By portraying his subjects as gentle, Peskine enables them to become unfettered by stereotypical, demeaning images that restrict them from being themselves.

Alexis Peskine, Ata Emit (to whom Belongs the Universe), 2017. Moon gold leaf on nails, earth, coffee, water and acrylic on wood, 250 x 250 cm. Courtesy October Gallery.

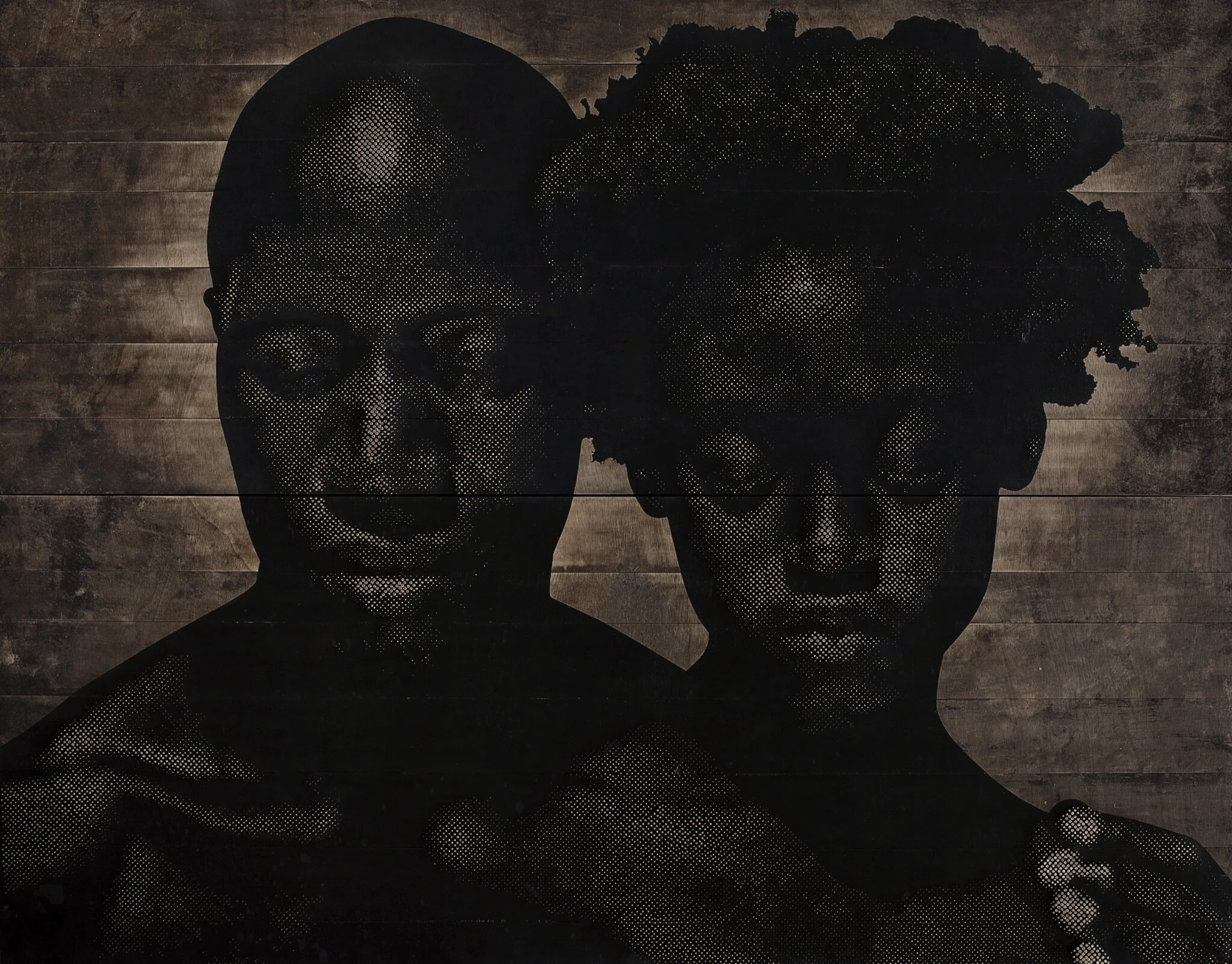

One of the most striking works in Power Figures is “Power”, a majestic portrait of a man and woman with their eyes closed. The man has his hand around the woman’s shoulder in a tender embrace. Peskine, however, reveals that the subjects are a father and daughter, and not a couple, as a lot of people assume. He explains that perhaps the nails make it difficult to make out the face of the young girl: “maybe it’s tricky with the nails...a child can very much look like an adult especially in something more approximative such as an image with nails.”

With “Power”, Peskine challenges the notion that links Black people with fatherlessness. “It’s reclaiming our parenthood, universal human values. Universal values are not generally attributed to us, especially Black fathers in the United States,” he explains.

Alexis Peskine, Power, 2017. Moon gold leaf on nails, earth, coffee, water and acrylic on wood, 195 x 250 cm. Courtesy October Gallery.

As well as exploring issues around the Black body and Black life, Power Figures is also “a synthesis of the injustices” that Black people face globally. We see this not only in the subjects, but also in the materials that Peskine uses to create his works. In these portraits, coffee is a symbol of the enslavement of Black people around the world. “Coffee, sugarcane or cotton are crops that were cultivated by our people that were enslaved so it goes back to human exploitation,” he says. “Even with colonialism and still today on the continent (Africa) … it could be cocoa, coffee, or rubber… all these things are mass produced and have to do with capitalism.” The incorporation of coffee in Peskine’s portraits highlight how Africa’s relationship with the rest of the world has been, and continues to be, predicated on exploitation.

The works in Power Figures extend beyond portraiture, and explorations of a traditional art practice. They confront, head on, issues of cultural representation and identity. Works such as “Power,” where the subjects are portrayed as embodying several characteristics at the same time, celebrate the complexities of the Black body. Power Figures questions prevalent, degrading images of Black life and, instead, counters them with dignifying images that honour Blackness. Peskine’s work demonstrates the power of imagery in advancing equality for Black people.

Regarding the Figure, The Studio Museum Harlem

Curtis Talwst Santiago, Por Que?, 2014, Mixed Media, 2 x1 1/2 x 2 1/2 in/5.1 x 3.8 x 6.4cm, © Curtis Talwst Santiago

This entrancing group show uses works from the museum’s permanent collection to probe the significance of the face and body throughout history. Drawings, paintings, sculptures and works on paper from the late nineteenth century to date explore various modes of figuration. From Curtis “Talwst” Santiago’s Por Que?, which portrays a scene from Eric Garner’s 2014 murder in a jewellery box, to Henry Taylor’s Homage to a Brother, a poignant tribute to Sean Bell who was killed by detectives on the eve of his wedding in 2006, the works in this exhibition echo current questions about institutional violence against Black bodies. But other works, such as Barkley Hendricks’ dazzling Lawdy Mama, an oil and gold leaf painting of a woman with an afro, exalt the Black body. This is a timely, stirring exhibition that powerfully demonstrates how figures and portraits document and shape Black identities.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Lawdy Mama, 1969. Oil and gold leaf on canvas. 53 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The Sellout, Paul Beatty

Winner of the 2016 Man Booker Prize, Paul Beatty’s The Sellout is a gripping, ingenious satire about race relations and Blackness in America, that lampoons and questions the idea of progress. It recounts the efforts of Bonbon, a young African-American man, to put his hometown of Dickens back on the map. Bonbon pursues his goal in the most scandalous way: bringing back slavery and segregation. He is eventually tried in the Supreme Court. While Bonbon’s tone on race is sombre and cynical, he often coats his pessimism in humour: “believe me, it’s no coincidence that Jesus, the commissioners of the NBA and NFL, and the voices on your GPS (even the Japanese one) are White,” Bonbon says. The Sellout dissects and reveals the fallacies of multicultural America, reminding us that “history is the things that stay with us.”